LNG Tankers and Rhode Island's Economy - Oil and Water?

Anyone who lives in or near Rhode Island knows Narragansett Bay is our centerpiece - the State's dominant feature around which we all live, and from which many of us make a living. So the prospect of LNG tankers plying our waters has drawn much attention, with safety and environmental concerns at the forefront: Safety, because LNG tankers carry tremendous combustive potential should an accident or attack occur. And environment, because to accommodate tanker passage, various areas of the Bay could need dredging, including some where the bottom is laced with industrial waste, the unleashing of which could threaten shellfish beds and fish hatcheries for decades to come. While safety and the environment compel by shear drama, a third issue looms - less sensational but equally pressing - the potential impact to RI's economy.

Tanker 'LNG Rivers'

The exact contribution of Narragansett Bay to RI's economy is difficult to measure. Conservative estimates look at the economic impact of just those industries that directly derive income from the Bay. These are sometimes referred to as the "Marine" or "Bay Cluster," and they include:

|

Based on census statistics from 1997, the Bay Cluster generated $426-million in business and employed over 8-thousand people who earned wages of $227-million. These seem like large numbers, but in 1997 they only accounted for 2% of RI's total economic output or gross state product (GSP), and 3% or RI's total employment. Of course, RI's economy has grown since 1997. According to the Federal Bureau of Economic Analysis, RI's GSP in 2004 was just over $41-billion. If we want a gross reinterpretation of the 1997 census, 2-percent of $41-billion comes to $820-million. But even this figure seems conservative. For instance, in 2002 the RI Senate Policy Office prepared a report, "The Marine Cluster, An Investment Agenda for Rhode Island's Marine Related Economy," in which they said, "The EDC Rhode Island Tourism Division reports the state's travel and tourism industry set a record in 2000 sales revenues of $3.26-billion." While it's difficult to parse this figure into components the Bay might account for, it seems plausible to assume a major portion of this travel/tourism revenue must derive from the Bay. Recognizing once again that travel/tourism has only grown, one might infer that this sector alone could surpass the 1997 estimate for the entire Bay Cluster.

Such disparities in measurement present a real problem. Precise economic numbers are hard to quantify, especially when trying to measure the indirect benefits related to 2nd tier industries that do business with members of the Bay Cluster, or the 3rd tier ripple effects of monies earned within the cluster but spent elsewhere on things as unrelated as groceries. Economic interactions can work like a row of dominoes, so the proposed LNG terminal in Fall River puts a premium on determining the potential impact of tanker traffic to the Bay's economy. To do so, a number of new studies are in the works:

|

As results from these studies become available, they will be poured over with keen interest. Whether a $1-billion economic engine or something possibly much larger, anything that could destabilize the Bay's economy and jeopardize the livelihoods of thousands of Rhode Islanders could certainly impact the economy of the entire state.

How could LNG tankers pose such a threat? In the latest version of the project being planned for Fall River, as many as 200 LNG tanker deliveries would be made in a year. That's 200 inbound tanker transits plus 200 outbound, for a total of up to 400 transits every year. This volume of traffic would make LNG tankers the predominant commercial traffic on the Bay and bring along with it some unique requirements. LNG tankers are so big they can only move on the Bay when the tide is rising - this to ensure the channels are deep enough to accommodate safe passage. And being "vessels of interest" - a.k.a. potential terrorist targets - LNG tankers require extensive security measures:

|

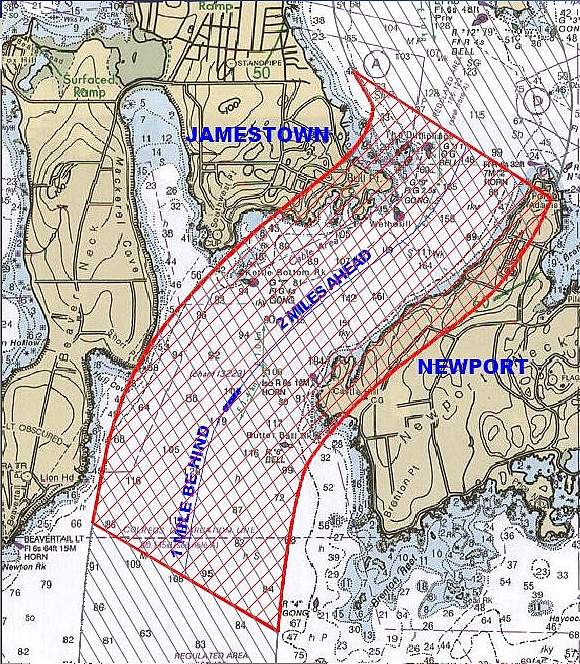

LNG Tanker "Footprint, courtesy of Aquidneck Island Planning Commission

That's a big "footprint." In fact, the security cordon is so big, there's almost no place on the Bay where it wouldn't overlap shore to shore. Thus an LNG tanker's security cordon could travel like a slowly moving blockade, forcing other Bay traffic aside as it plods the 2-hour trip from the Bay's entrance to Fall River. Then if you factor in the tide requirements for transit while laden, the volume of tankers proposed, and the need to travel in daylight, that doesn't leave much to guesswork regarding their schedule. So much for traveling "unannounced." No, the real guesswork has to do with the "footprint" itself - how big will it actually be?

Tanker security requires the coordinated efforts of several entities, including the local authorities, the tanker's owners, the Marine Pilot's Association, and the United States Coast Guard, but final command belongs with the Coast Guard alone. For Narragansett Bay, the chain of command leads to Roy A. Nash, Captain of the Port, US Coast Guard Sector Southeastern New England. He has discretion over whether a security zone will extend 2 miles ahead, 1 mile astern, and a-thousand yards either side, or whether half a mile bow and stern, and 300 yards either side would be adequate. He also decides whether the zone should completely exclude other traffic, or whether certain vessels might be allowed to keep moving based on their relative threat.

Tanker 'Matthew' under watchful eyes, www.ferc.gov (courtesy US Coast Guard)

As a practical matter, the shear volume of summertime traffic on Narragansett Bay would make enforcing security zones a Herculean undertaking. According to Howard McVay, President of the Northeast Marine Pilots Association, "The security zone is there to prevent boats from just sliding down along side of the tanker." Indeed, Edward LeBlanc, Chief of the Waterways Management Division, US Coast Guard Sector Southeastern New England, suggests the security zone need not unduly delay other vessels. "The procedures for LNG tankers would be similar to the procedures for the LPG tankers that already come into Providence," he states. "We've never had a complaint from a maritime enterprise about delays due to LPG transits." But then LPG tankers only come in once a month. According to Howard McVay, when an LPG tanker comes in, "Other commercial traffic has to stand off to the west of Gould Island for up to 2 hours."

If such delays were to become a frequent event, they would be far more than a nuisance. Any traffic on the Bay, be it commercial or recreational, would have to adjust - perhaps altering course to clear the security zone, heaving-to and holding position, or just staying in port while the LNG tanker proceeds. Whether a frequent annoyance or a protracted halt to activity, the issue depends on how rigidly the security zone would be enforced, and how the perceived threats from marine traffic would be judged. For obvious security reasons, these questions present an impenetrable fog, and regardless of any light the Coast Guard might shed, enforcement procedures could shift on a regular basis. With so much built-in uncertainty, it would be shortsighted to plan for anything less than full enforcement when assessing the impact to the Bay.

Newport Harbor Tour

And what of the bridges that cross over the Bay? The Rhode Island Bridge and Turnpike Authority has announced it will close both the Pell and the Mt. Hope Bay Bridges when an LNG tanker comes in. This too is cause for concern. How would bridge closures impact commuters, delivery vehicles, and emergency vehicles? A recent study done by the Aquidneck Island Planning Commission, "LNG Traffic Impact Assessment: Newport/Pell and Mt. Hope Bridges," predicts traffic delays of between 20 and 45 minutes at the Pell and Mt. Hope Bridges respectively. If this happened on a regular basis, would it discourage summer tourists enough to go elsewhere? If so, not only would RI lose those tourism dollars, but the Bridge and Turnpike Authority would also need to make up for the shortfall in tolls.

While we can't say exactly how tanker-related delays would impact the Bay economy, there's plenty of evidence that people are nervous. According to Todd Johnston, Head of 'Doyle Sails RI,' "There's almost no question the premier racing events on the Bay would all go away. You can't just stop a race once it's started." And Lisa Harrison, owner of 'Only In Rhode Island' in Newport, worries about the impact on tourism. "Will the cruise ships still come to Newport?" she wonders. "I think LNG tankers would adversely affect Newport's economy and the quality of life on the Bay." These and similar sentiments from many others point to the potential loss of thousands of annual visitors who come to Rhode Island to enjoy Narragansett Bay, and who collectively pump millions of dollars into RI's economy - spending money on restaurants, hotels, bars, marinas, summer rentals, fishing trips, charters, gifts, and the list goes on an on.

According to Keith Stokes, Executive Director of the Newport Chamber of Commerce, "Over the years, great effort has gone into re-aligning the Bay towards passive recreation and away from commercial activity." He thinks LNG traffic could throw that all out of balance. "Proponents of the Fall River facility make comparisons to other bay communities with dual-purpose waterways, but their comparisons are made to much larger bays, where it's easier for communities to mitigate the commercial impact. By introducing large volumes of LNG traffic to Narragansett Bay, the Bay's usage would be suddenly flip-flopped." There's little doubt a change of this nature could dramatically change the Bay's character and how it generates income for Rhode Island.

Looming Energy Crunch for RI - and the Country:

Any impact that LNG tankers might have on RI's economy should be weighed

against the potential benefits of expanding the region's energy resources. At

present, Rhode Island's energy needs - residential and commercial combined -

are predominantly met by burning oil and natural gas, each in roughly equal

measure. According to Janice McClanaghan, Chief of Energy and Community

Services for the Governor, "The emergency oil reserves for the New England

- 10.5 million gallons - are located in Providence, and in addition to that we

have heating oil reserves for RI that will last 5 to 6 days." So in a

severe crunch we have backup. "As for natural gas, we're at the end of the

pipeline," she continues. "There is what there is. So when it gets

really cold and more gas is needed, that's when we have to supplement with

things like LNG." Indeed, Keyspan Energy owns and operates a "Peak

Shaving Facility" in Providence that does supplement what "there

is" at the end of the pipeline. Supplied with LNG delivered by

tanker-trucks, the facility is used for backup during the coldest days of

winter and is critical to current operations. In the face of growing demands,

however, its limited capacity is no long-term solution. "We lucked out

last winter that it wasn't as cold as predicted," concludes McClanaghan.

"We could easily have had a natural gas shortage. If that happened, first

priority would be given to residential customers - to ensure they have heat -

then commercial customers, and utilities would come last."

Utilities - electricity. According to David Graves, Senior Media Relations Representative for National Grid, "Demand for electricity throughout the US is predicted to rise between 2.2 and 2.7% annually for the foreseeable future. For the 12 months ending March 31, 2006," he continues, "RI consumed 7,963,735,689 kilowatt-hours of electricity." The types of power plants used to generate the electricity we use, in order of their percentage contribution, include:

|

This is an interesting list, but it's especially worth noting that natural gas is used to generate one-third of RI's electricity needs. That's because virtually all of our in-state generation capacity uses natural gas. According to Ken McDonnell, spokesman for ISO New England, "Rhode Island's peak generation capacity (akin to an automobile's rated horsepower), is expected to be 1,808,000 kilowatts for 2006. At the peak of last summer, the state's demand reached 1,845,000 kilowatts," he continues. "On average, RI's demand for power ran between 975,000 and 1,000,000 kilowatts." While these numbers seem to indicate we have sufficient generation capacity to meet all but our peak-demand periods, quite the opposite is true.

"Because gas-fired power plants are amongst the most expensive to operate," says Andrew Dzykewicz, Chief Advisor to the Governor On Energy, "many of our in-state facilities are used intermittently - more to help meet peak-load demands than to run on a constant basis." Consequently, much of the electricity RI uses comes from the regional grid.

"Rhode Island's power generation capacity is so dependent on natural gas," says Ken McDonnell, "if a natural gas shortage occurred during a period of peak demand for electricity, that would hurt. This past winter had us especially worried," he concludes. "Between the damage from hurricanes in the gulf last summer, and the forecast for a very cold winter, there was a real chance of a shortage. Had that happened, then yes, an additional source of LNG in the region could have been a good thing."

Alternatives:

While energy needs throughout the US continue to grow, many coastal communities

are reluctant to host LNG terminals and accommodate tanker traffic. The reasons

are many, including economics, but the most consistent objection is safety,

even though LNG tankers are safer than many other types of tanker. For

instance, the tanks on an LNG tanker are pressurized with inert gas to displace

any oxygen. According to Howard McVay of the North East Marine Pilots

Association, "You can drop a lit match into one of these tanks, and the

match will go out long before it reaches the LNG." Safety systems like

this, and redundant backups, are designed into every aspect of an LNG tanker.

But since 9/11 that isn't enough. Today, "safety" means being able to

withstand something akin to the attack on the USS Cole. Fortunately, no such

attack has yet tested the double-hulled integrity of an LNG tanker, but few

deny these tankers make high-profile targets, especially in close proximity to

a densely populated area. That's why LNG tankers require so much security. When

a tanker comes in, patrol boats keep traffic away, bridges are closed, and

helicopters keep watchful eyes on the sky and distant waters. But even the best

security cannot guaranty that a determined group of terrorists won't get a

plane or a boatload of explosives near enough to wreak havoc.

Given the remote but very real potential for disaster, one has to wonder if bringing huge shipments of LNG through a small inland bay and up to a city is really worth the risk? The answer would patently seem to be "no," not when better alternatives exist - offshore terminals for one. For many years, the oil industry has made use of offshore terminals to offload petroleum products from tankers. The same can be done for LNG, as proven by the Gulf Gateway Energy Bridge Terminal, the world's first offshore LNG terminal, located 116 miles off the Louisiana coast. With offshore terminals, the tanker pulls up to a giant offshore buoy or platform; the LNG is pumped into holding tanks and/or re-gasified and pumped ashore via pipeline. With a system like this, the security issues and attendant costs of tankers transiting or berthing near coastal populations goes right down the drain.

Gulf Gateway Offshore Terminal, www.excelerateenergy.com

Another alternative could come from our neighbors up north. According to Andrew Dzykewicz, "Offshore terminals could look good, but none have been proposed for RI. However, Canada is willing to build the necessary facilities - the LNG terminals and pipelines - to accommodate most of New England's future natural gas needs." This is the most attractive alternative to Fall River that has been proposed, and Mr. Dzykewicz is working on behalf of the Governor to help cultivate the scenario. "Because we do need to augment our supplies," Dzykewicz concludes in a familiar refrain. "We've come close to shortages, and then we'd be stuck having to divvy limited supplies. That wouldn't be pretty."

What Happens Next?

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) has already approved the Fall

River project. However, two pieces of legislation, one being considered in

Rhode Island and another already passed in Massachusetts, have thrown up

potential barriers:

|

Because of the changes to the Fall River proposal made necessary by retaining the Brightman Street Bridge, the door has been opened to further review by FERC. As of this writing no decision has been taken. With regards Rhode Island's proposed legislation, passage would certainly increase the odds of forcing the issue into court. As noted in the Providence Journal, "A similar bill was approved by the Massachusetts legiulature but is now being challenged by federal officials on constitutional grounds."

Editorial Thoughts:

While they may feel good in the short run, throwing up legislative roadblocks

can hurt in the long run. Moves like these can raise hackles at a time when

cooperation is desperately needed. It's incumbent upon us - the consumers and

voters of this country - to realize that "big energy" - in this case

Hess Oil - isn't always the "bad guy." They're trying to meet a real

need - solve a problem - which we ourselves have created. And we must recognize

that leaving this problem unsolved could create a major economic and

humanitarian disaster in its own right. For the next decade at least, we need

to increase our supplies of LNG. That said, given the security, environmental,

and economic concerns over the current proposal for Fall River, it's difficult

to imagine how the project can work. Even if FERC reaffirms its approval, the

whole affair will end up in court for a long and costly battle. In either

event, compromise is needed.

While it would be nice if state and federal officials could work out a deal whereby Canada would satisfy our expanding appetite for LNG, the market for LNG is global and competitive, and no rational authority would lock up a deal without taking competitive bids. So here's a suggestion for Hess Oil, AKA Weaver's Cove LLC: Withdraw your proposal for an LNG tanker terminal in Fall River, and come back with a proposal for an offshore terminal and pipeline that ties into the existing distribution system for natural gas. While the costs of an offshore terminal would be higher up front, the ongoing costs would likely be significantly less, and the good faith engendered by withdrawing an unfriendly proposal would help pave the way to a much smoother deal.

Looking beyond Fall River, it's interesting to note that industry experts have - until recently at least - predicted the price of LNG would fall as new supplies come on-line. But just as with oil, LNG is a limited resource, and in time the costs will inevitably rise. Like the dinosaurs they come from, fossil fuels will inevitably become a thing of the past, but for now we must use them as a bridge to better alternatives - like wind farms, solar power, safer forms of nuclear power, bio-diesel, hydrogen, improved methods of conservation, and so on. Unfortunately, we're long overdue for a national agenda that puts advanced energy initiatives amongst our nation's very highest priorities - along side some sensible compromise. Perhaps the current surge in oil prices - the second such shock in a year - will spark renewed interest amongst our leaders, including those who talk a good game but who then seem to throw up roadblocks when their backyards are involved. And the same holds for many environmentalist groups whose agendas are often so anti-compromise as to appear rabid for the sake of effect more so than to 'help save the planet.' It's time for all of us - the consumers and voters of this country - to demand more cooperation and less posturing from those in leadership roles. The real question is, are we a big enough People to do that?

Thanks to:

Thanks to all who've humored my questions to help develop this article. I've

tried to do justice to your trust. And special thanks to:

|

Copyright 2006, NetScribe